NYCHA, Circling The Drain

/From time to time I like to check in on the latest from the New York City Housing Authority. NYCHA (along with many other municipal housing authorities) is one of the purest examples in the U.S. today of socialist-model economic organization. The state owns the buildings; the residents pay deeply subsidized rents based on income; and the state takes full responsibility for maintenance and upkeep. Is there any reason why this might not work for the long pull?

When we last looked back in 2018, NYCHA had just been sued by the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York for failing to maintain “decent, safe and sanitary” conditions, including failing to remediate lead paint, failing to control mold and vermin, and failing to provide consistent heat, hot water., and elevator service. NYCHA had promptly settled that lawsuit with a Consent Decree in which it promised to spend some $4 billion of New York City taxpayer money to fix the identified problems.

In the intervening close to 5 years, NYCHA has been mostly out of the news. Surely, the large infusion of funds has turned things around, and all is now going smoothly? Sorry — that is not how socialism works.

On May 19 a civic organization called the Citizens Budget Commission has come out with a big Report on NYCHA with the title “Uncertain Future, Urgent Priority.” The Report is chock full of data and statistics on how things are going. The summary is, things have gone from bad to worse, and then still worse. Most importantly, nobody here cares about running a financially sustainable operation, so revenue dwindles while costs explode out of control. One can only conclude that the game plan is to engineer a real crisis to more effectively shake down the taxpayers for the really big bucks in the next round.

In privately-run rental housing, the rents must cover all of the costs — operating costs, taxes, debt service, and also capital improvements as they are needed — as well as profit to the owner, if any. At NYCHA, rents, such as they are, cover an ever smaller and smaller share of the operating costs, with nothing whatsoever for taxes, debt service, or capital improvements. Here is CBC’s chart of NYCHA revenues versus operating expenses:

Rent collections reached a peak in 2019, and then started shrinking in 2020 with the pandemic, and have continued to shrink at an accelerating rate through 2022. Federal subsidies increase, but don’t nearly keep up with rising costs.

At this point, collected rents cover barely a third of operating costs. It seems that the stated rent is now treated as merely a suggestion, with no effective penalty for non-payment:

Collections hit a new low of 63 percent in February 2023, down from 70 percent in February 2022 and 90 percent prior to the pandemic. . . . As of December 2022, 46 percent of NYCHA households were in arrears, having accrued $466 million in unpaid rent. . . .

Although the pandemic has ended, the new policy is to forget about evictions, even as nearly half of tenants have stopped paying rent:

Under the Transformation Plan, NYCHA has de-emphasized non-payment evictions in favor of working with residents to get on payment plans and to secure one-time hardship funding. Since then, NYCHA has followed through on its promise to avoid evictions. Between February 2022, when the eviction moratorium expired, and January 2023, NYCHA filed only 427 non-payment eviction notices, and 0 warrants for non-payment evictions have been executed.

Thus, with some 80,000 tenants in arrears, there have been only 427 non-payment proceedings. That is a sure-fire recipe for continued erosion of rent collections. Why would anybody pay in these circumstances?

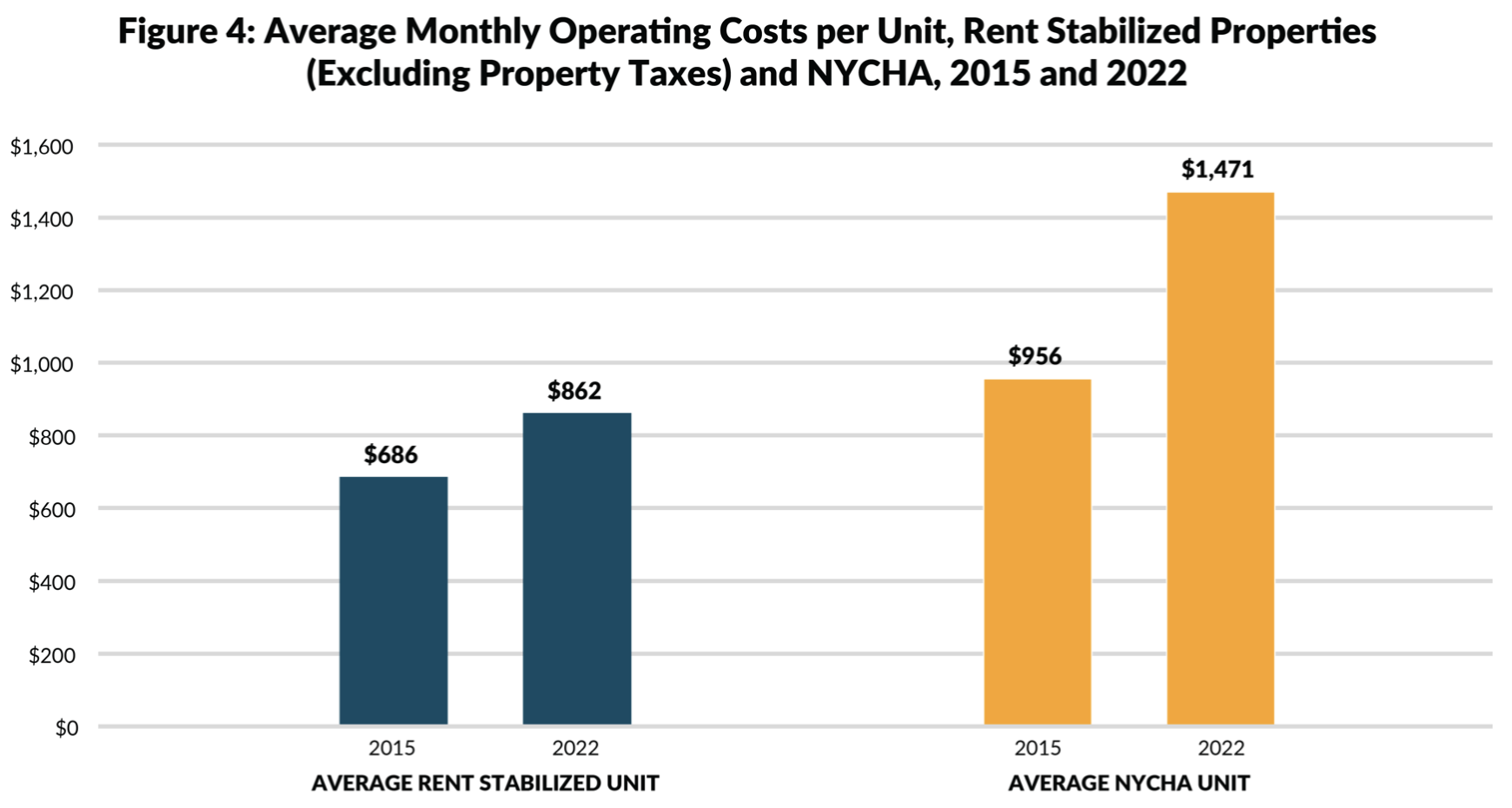

Over on the cost side, it seems that NYCHA’s costs of operating a unit are about double those of private landlords on a per-unit basis:

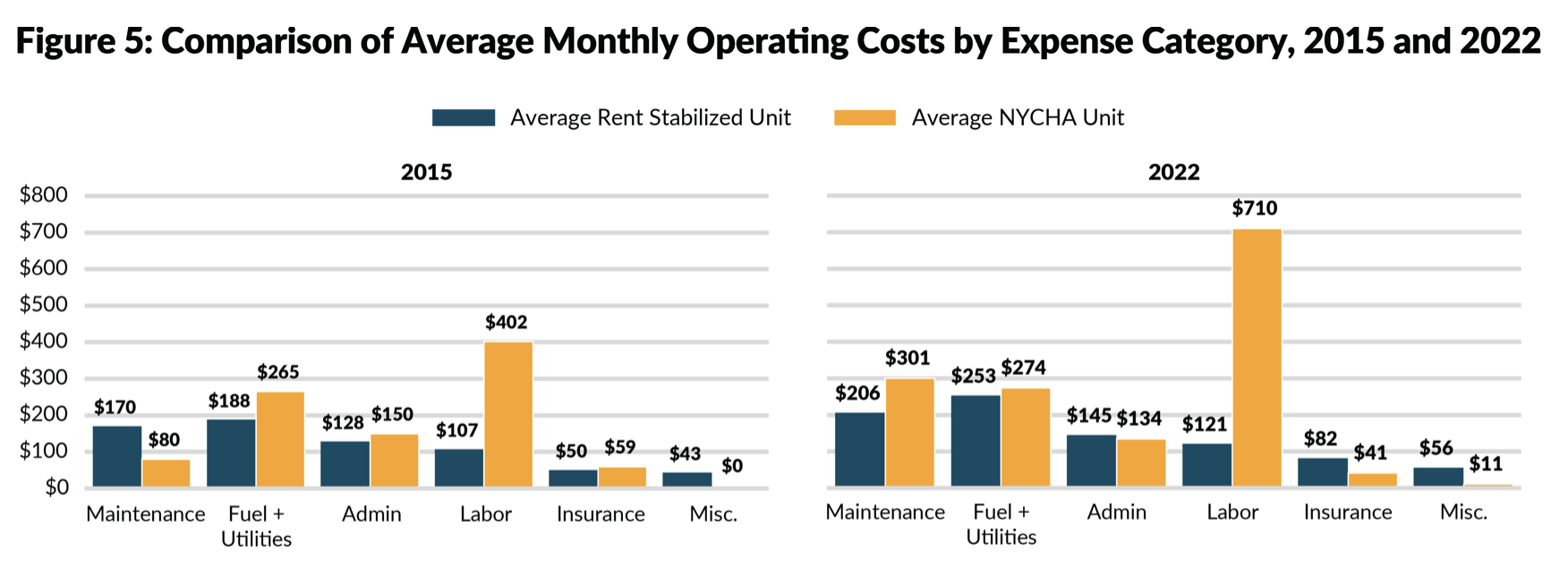

Nearly all of the cost differential is in the category of labor costs, where NYCHA’s expenses per unit are about six times those of its private counterparts:

The CBC concludes that the large majority of NYCHA’s units are rapidly approaching a “moment of reckoning,” where “redevelopment would be more cost effective than repair.”

Once again, a seemingly well-intentioned government program has ended up leaving large numbers of the intended beneficiaries in a completely untenable situation. At this point, it’s only a question of how and when this situation comes to its final collapse.